There is a piece of writing from e.e. cummings where he says: ‘To be nobody-but-yourself – in a world which is doing its best, night and day, to make you everybody else – means to fight the hardest battle which any human being can fight; and never stop fighting.’

I know he is referring to the life of a poet – indeed, the title of this piece is ‘A Poet’s Advice’. However, when my partner showed me the excerpt in his book, I felt it applied to something else, and thus I write it here.

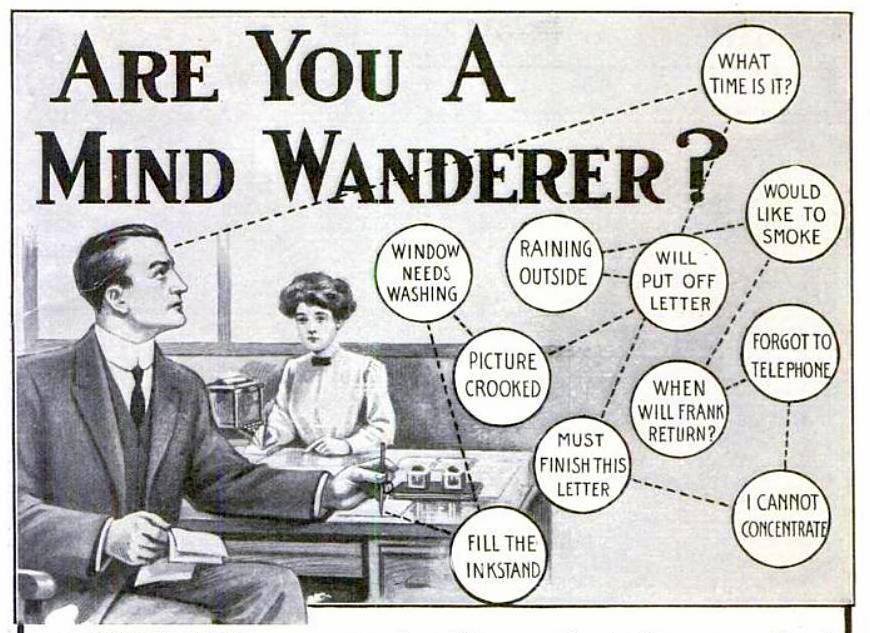

I’ve been on a road to forgiveness of some sort. For a large portion of my life, certainly since I was small, I’ve felt like I’ve been on some sort of test run. As if I’ve not really been present throughout my days and that, at some point in the future, everything would simply click into place – the video of my life would suddenly come into focus after buffering away for years. This isn’t to say that I haven’t felt joy, anger, euphoria or any other emotion during that time. In fact, I’ve felt them in abundance. I just couldn’t grapple with why I felt them so intently, when the smallest thing – a delayed train or a sudden noise – would send me into a spiral, much to the bemusement or concern of those around me. I’ve learned this is called disassociation, that fog-like haze you might feel when your brain goes into overload. In certain disassociate states I can float above myself, looking down at the room I’m in; a kind of lucid dreaming. Curious and calming during a cramped train ride, not as optimal during a Zoom work call.

They say trauma starts in childhood, so here’s a tale. I remember my teachers in primary school, exasperated, asking me why I didn’t want to play with the other children, not understanding that I just wanted to immerse myself in my intricately detailed make-believe cocoon, all by myself, or hauling me out of a toy box during a fire drill where I’d hidden for hours. I just wanted to remain in my safe little world, where I could make up my own stories and see things in a way that I understood. In many ways I still revert to this fantasy now, as an adult. Or teenage me at secondary school who, despite a close-knit and loving friend group and reasonable academic success, hated myself; was unable to understand why I felt so vastly different from her peers and experienced a creeping dread in every social situation; who cried in frustration when she didn’t understand a mathematical problem, picked at my skin or pulled at my hair during exam periods. I remember going to my GP during my first weeks of university in a complete state, tearfully begging to be referred to a therapist after weeks of panic attacks and being unable to speak – only to be handed a leaflet about meditation and print-out of a list of therapists I could try calling, but ‘they probably wouldn’t take me’ as I wasn’t Dutch. My GP told me to try yoga, to be grateful that it was ‘all in my head’ and not in real life, and to stop reading up my symptoms on the internet. I dropped out of my bachelors degree shortly after that visit.

But now, when I think about that little girl who just wanted to be alone, who was scared of loud noises and couldn’t understand the games the other children were playing, I feel my heart swell with sympathy instead of embarrassment and resentment.

I’ve learned that this world is not built for neurodivergent people, as much as corporate diversity and inclusion committees may have you believe. The e.e. cummings quote at the beginning of the piece is a good reminder of this. Because in a world that constantly pressures you to fit in, to play the game and get on with things, those with differing brains suffer. I read that up to 85 per cent of neurodivergent adults are unemployed, and that most studies on neurodivergent disorders are carried out on white, European, white, teenage boys. Most women who are diagnosed autistic or ADHD usually spend years suffering with depression and anxiety, and are often brushed off as just being emotional until they are finally diagnosed in their late twenties. As a white woman who is only now being able to access these vital health services, I cannot imagine the pain and systemic ignorance towards men and women of colour going through similar battles with their own neurodivergence journeys. While learning about your neurodivergence can be liberating and healing, it’s also an exhausting, expensive and time-consuming journey. It shouldn’t have to be – but I’ll save my rant about the Dutch and Irish health services for another time.

Some people say that neurodivergence is a gift, and in some instances, I’m inclined to agree. I am able to enjoy music and art to an ecstatic degree, recanting melodies and details from songs and books that I read years ago. I’m creative and can go into extreme detail about subjects I’m interested in, sometimes to the annoyance of others – but let me live. After all, who doesn’t want to know my bizarre expertise on shows like Arrested Development? I’m a good listener and love helping people with their problems, even if I can’t reciprocate in the same way with my own. I can pick up on people’s emotions – my mum calls me a canary in a coal mine – and can be empathetic to a fault.

But there are times where it cripples me, and when it comes with not-so-quirky traits. Certain social situations can absolutely drain me, especially if I’m with large groups of strangers having multiple conversations at once. I flinch when people who aren’t my closest friends touch me, which can lead to odd looks. When I get sick, my anxiety takes over, and I find myself needing to call in sick from work not for physical but for mental stress. When I get overstimulated around others I shut down, often experiencing mutism and can come off as rude and snappy. I’m lucky that my closest friends understand this about me and won’t judge, but it doesn’t make it any easier. I often feel like I’ve aged a lot in the last few years, opting to spend my weekends in a low-key manner and going to bed early. I understand this is what I need to do for my body and brain, but I’d have liked to be a bit more rock-and-roll in my twenties. That’s just something I have to accept, and at the end of the day, it’s okay.

The world may not be made for us, but you can make it work for you. In fact, demand that it does. Ask for accommodations at work if you need them, and confide in your closest friends when you’re struggling. You don’t have to be an activist for neurodiversity, but learn to advocate for yourself. Most people’s ideas of autism and ADHD are outdated and archaic, often unintentionally, so encourage those around you to listen. And at the end of the day, telling people your brain works differently doesn’t change much, but it’ll give you a sense of freedom and safety. Your real friends will take that on board and be your buffer, your security, your protectors, as you are for them.

The rest of the e.e. cummings quote goes:

‘Does this sound dismal? It isn’t.

It’s the most wonderful life on earth.

Or so I feel.’

I think I can relate, to some extent.